"I Hope Never to Return" — Frida Kahlo, Commodification, and My Complicity

- Adriana Leos

- Feb 21, 2025

- 5 min read

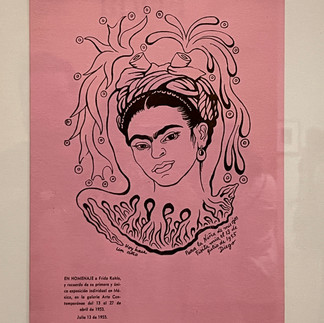

A few weeks ago, I visited the Frida Kahlo: Beyond the Myth exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art. Walking through the gallery, I was surrounded by vibrant portraits, intimate self-reflections, and the undeniable presence of a woman who defied categorization.

---

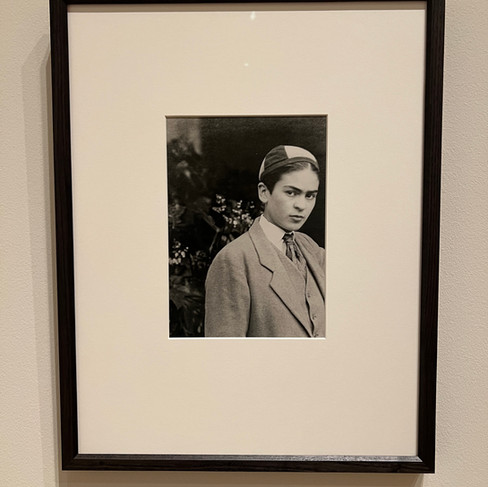

Frida Kahlo was born July 6, 1907 in Coyoacán, México to Matilde Calderón and Guillermo Kahlo, a German professional photographer. Frida's life was marked by suffering at an early age. At six, she contracted polio, which permanently impaired movement in her right leg. Later, at the age of 19, the bus she was riding in collided with a street tram; a long metal rod tore through her midsection and Frida suffered serious injuries.

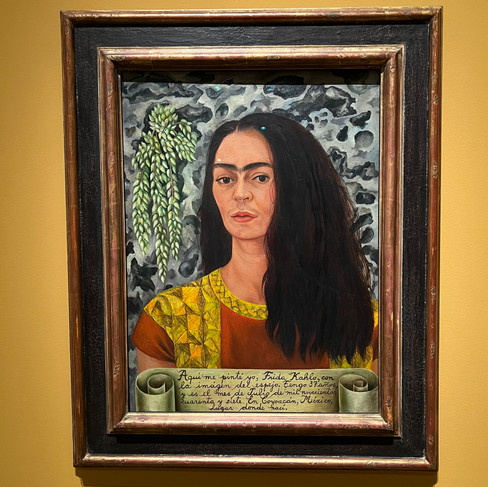

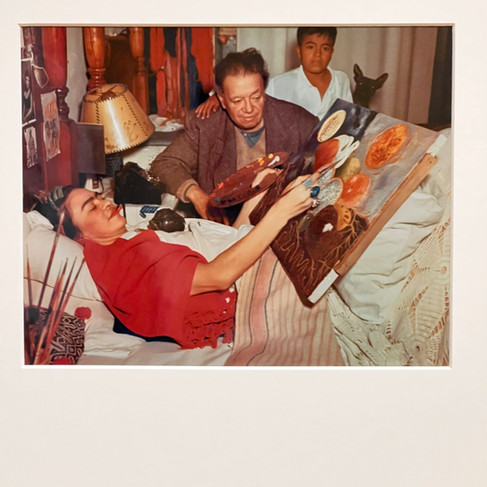

Frida's ambition was to study medicine but during her long recovery period, painting became a solace and what sustained her during this time. Her parents gave her a lap easel so she could paint while bedridden, and they mounted a mirror in her bed's canopy to help her paint her own face. And as the daughter of a professional photographer, Frida was familiar with posing for a camera but now she turned her attention to painting her own portrait.

Her romantic life was no less turbulent. After first encountering Diego Rivera in 1922, they officially met in 1928 when Frida asked him to critique her work. They were married in 1929, and she terminated her first pregnancy after Diego insisted they remain childless.

Together, in 1930, the two of them traveled to San Francisco, where Diego completed three mural commissions. In 1932, they traveled to Philadelphia and Detroit, where Frida terminated her second pregnancy and she soon after returned to México to recuperate.

Her mother passed away in 1933, and Frida suffered several setbacks including major surgery on her right foot, and her husband's infidelity with her younger sister, Cristina. Frida retaliated against Diego's betrayal by taking several lovers. When she became pregnant a third time, she again chose to end the pregnancy.

After divorcing in 1939, Frida and Diego remarried in December 1940.

Frida became a professor of painting, but her increasingly poor health often confined her to bed and required students to attend class at her house. By 1944, she began wearing a steel corset to support and immobilize her back. In 1946, incessant pain prompted her to travel to New York for a spinal fusion, but the surgery and a series of subsequent operations were unsuccessful.

Finally, in 1948, she endured Diego filling for divorce two different times, both to wed two different women.

He ultimately rescinded the divorce papers and remained with Frida. These years of immense physical and emotional pain also surrounded some of her most powerful self-portraits.

By 1951, Frida could only paint while lying down, propped up by pillows (see image above).

She later died at home in Coyoacán on July 13, 1954.

The last words in her diary read: "I hope the leaving is joyful - and I hope never to return."

---

I wanted to share a bit of Frida's life history to provide a deeper understanding of the life she endured. Regardless of how one views her, it’s undeniable that her journey was marked by immense trauma and pain (both physical and emotional). Yet, beneath all the chaos, her deepest longing was simply to find peace.

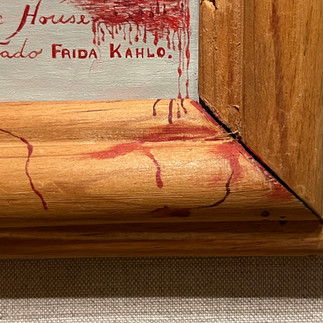

And here’s where my discomfort settles. This piece (below) has lingered with me since leaving the museum, and specifically the quote from one of her final diary entries "I hope the leaving is joyful—and I hope never to return."

I stood there, thinking about those words—while standing in an exhibition that quite literally summoned her back—her likeness, her pain, her resilience—packaged into an experience with a gift shop at the end.

And that’s when the weight of my own complicity hit me. I have a tattoo of Frida on the back of my right arm. And I also own Frida merchandise: a tote bag, pencil holder, t-shirt, magnet, postcards. Little pieces of her face scattered across my life like souvenirs of admiration. And yet, what does it mean to admire someone whose final wish—never to return—has been blatantly ignored for the sake of capitalistic gain?

Frida Kahlo was an anti-capitalist. She despised consumer culture and lived a life defined by resistance. And yet, in death, she has become exactly what she stood against: a brand. Her face, now a logo. Her suffering, aestheticized. Her radicalism, softened into marketable empowerment.

It’s easy to point fingers at corporations, museums, and retailers profiting from her image. But the truth is, I’ve played a part, too. Every time I swiped my card for another Frida-adorned product, I participated in the commodification of a woman who likely would have hated everything about it.

I wonder how she would feel knowing someone has her likeness tattooed on their arm? Flattered?? Disgusted???

And it’s not just Frida. Modern artists and creators, especially those from marginalized communities, often face the same cycle. We see it happen all the time. Their work gets celebrated, extracted, repackaged, and sold—often without their consent or fair compensation. What starts as authentic expression becomes another cog in the consumer machine.

So, what now?

I’m writing this because I’m still wrestling with the dissonance of loving an icon while recognizing how that love has also been shaped by capitalism. I also still struggle with the idea of "separating the art from the artist."

And look I get it. We live in a capitalistic society, and I too participate in it every single day. I’m not here to preach from some pedestal. Maybe my first step is simply acknowledgment. There's no conclusion of this blog, the point is to just be. A space where I can freely share thoughts and ideas because I don't have many other places to do so.

I also frequent museums often, and I don't plan on stopping anytime soon. Some can argue that that's also contributing to capitalism. Which yes, obviously. But how else am I to see and engage with art to even spark these types of thoughts and questions in the first place?

Maybe then the next step is being more mindful about how I engage with art and the legacies of artists—not just as aesthetics, but as people with values, struggles, and, sometimes, final wishes to consider.

Frida hoped never to return. Yet here she is—on my arm, in my home, in pictures and videos I've posted to Instagram and TikTok, at the checkout counter at the gift shop. The question I’m then left asking myself is: How can I continue to honor her in a way that lets her rest while still appreciating her art?

x

Comments